The Rattling Mist o Cramond Shore

When haar creeps in across the Almond’s mouth,

An auld grey breath frae Forth tae sodden land,

The shells begin tae whisper, north tae south,

Their rickle-ruckle voice nae soul can stand.

Lang syne in Cramond, where the tides confide,

A mason named James Walker dared tae ken

What walked wi Widow Macniven at tide

A thing nae made by God, nor shaped like men.

He named the shellycoat, and thus was sealed

His doom, as clackin shells closed in his ears.

They found him drowned, wi mussels as his shield,

His face a mask of silence, wide wi fears.

So mind thy tongue, where sea and river meet

For even names may draw death to thy feet.

————–

Lang syne, whaur the River Almond meets the Firth o Forth, the wee village o Cramond lay wrapped in mist and mystery. The haar would roll in frae the sea, a thick smoorin fog that cloaked the shore and whispered wi the voices o the unseen. Folk kent well that the haar was nae mere weather—it carried stories, warnings, and sometimes, somethin far darker.

It was the year seventeen hunder, an the village was peaceful enough, save for the stories that clung tae the wind like seaweed. Among the folk lived James Walker, a stane mason wi fingers deft and heid fu o quiet thought. He kept tae himself mostly, but on a cauld morning in the market square, he let slip a word that stirred the kirk session and the village alike.

“I say the widow Macniven is a shellycoat,” James declared, loud enough for all to hear.

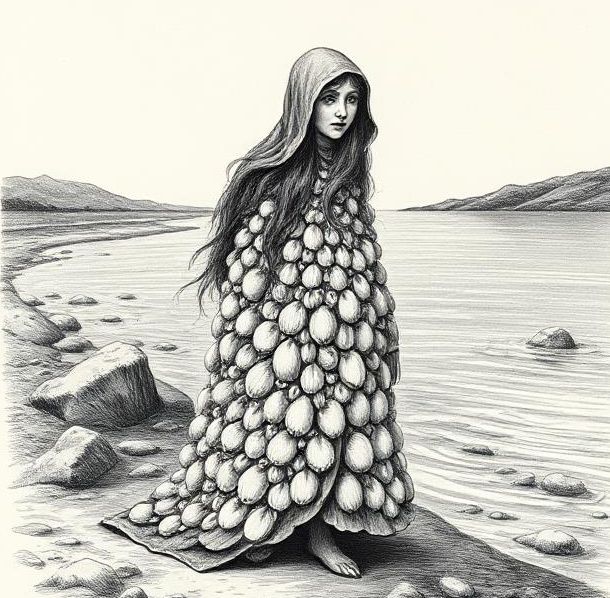

The elders exchanged uneasy glances. The word “shellycoat” was seldom spoken openly. It meant an ill spirit—an auld creature said to haunt the shores, covered in rattlin shells that clicked wi the tide, its voice a wet, sorrowful chuckle. Some said it was a trickster, others a warning, and some whispered it was a curse.

The kirk session called James before them, stern faces illuminated by candlelight. Reverend Ainslie spoke gravely, “James Walker, ye will answer for this slander. What mean ye by ‘shellycoat’? Speak true, for the eyes o the Lord are upon ye.”

James stood tall, though a shadow danced in his e’en. “I speak what I saw,” he said. “The widow, she walks the burnside at dusk, murmurin words nae man should ken. Behind her, I’ve seen a figure—no man, no beast. Its coat rattles wi shells, an its legs are thin as driftwood.”

The room grew silent but for the crackle o the fire. Some scoffed, but others looked grave, remembering tales their mither and faither told by the fireside. “The shellycoat is no just a tale,” whispered Maister Laird, “It’s a shadow that bides where water meets land.”

Widow Macniven herself didna appear at the session, and from that day, she walked wi a stoop, as if burdened by unseen weight. The village folk whispered behind cupped hands, wary o the mist and the secrets it hid.

As autumn deepened, the haar thickened, and the nights grew lang and chill. The bairns darednae wander near the tide pools, for they said the shellie coat’s footsteps clicked like the rattlin of shells in a shoggin bag, a sound that chilled the very bone. James grew obsessed, wandering the shore at twilight, listenin for the eerie clatter.

One moonless nicht, he followed the widow to the burnside, cloaked in mist and shadow. He saw her gather driftwood near the tidal pools, her voice low and strange, whispering in tongues no soul ken. Then he heard it—the clack and clatter of shells, soft but certain, like dry bones knocking together.

What came next is lost tae memory, for when dawn broke, James Walker was found lyin in the shallows. His face was pale as the moon, his mouth agape, and his ears and eyes packed wi small white mussel shells, as if to silence him forever.

The kirk elders buried him swiftly, speakin few words. Reverend Ainslie called him “a troubled man lost tae his own dark imaginings,” but the village knew better. The mist seemed darker, the clatter louder, and the bairns dared never stray close tae the water’s edge.

Widow Macniven left Cramond soon after, sayin the salt air made her lungs ache. But some said she fled frae the shellie coat that walked wi her, a shadow born o the sea and sorrow.

The tale lingers still. When the haar rolls thick ower the village and the moon hides behind clouds, folk say ye can hear the clatter o shells and a low, wet laugh driftin frae the tidal pools. Is it the shellycoat? A warning? A curse? Or just the wind and water singin tae themselves? No one kens for certain, but the story warns: beware whaur water meets land, and mind the words ye speak—for some names summon shadows that will never leave.

For generations, the folk o Cramond have passed the story by the fireside, a tale both warning and mystery. Some say the shellie coat is no beast, but a mirror tae our ain fears, takin shape in the fog where land and sea entwine. Others believe it still haunts the shoreline, waiting for the unwary or the bold.

And if ye wander by the River Almond on a misty nicht, listen for the soft rattle o shells on the rocks—and the laughter that follows.